Research Features

Roadmap for Naming Uncultivated Archaea and Bacteria – The long-standing rules for assigning scientific names to bacteria and archaea are overdue for an update, according to a new consensus statement backed by 119 microbiologists from around the globe.

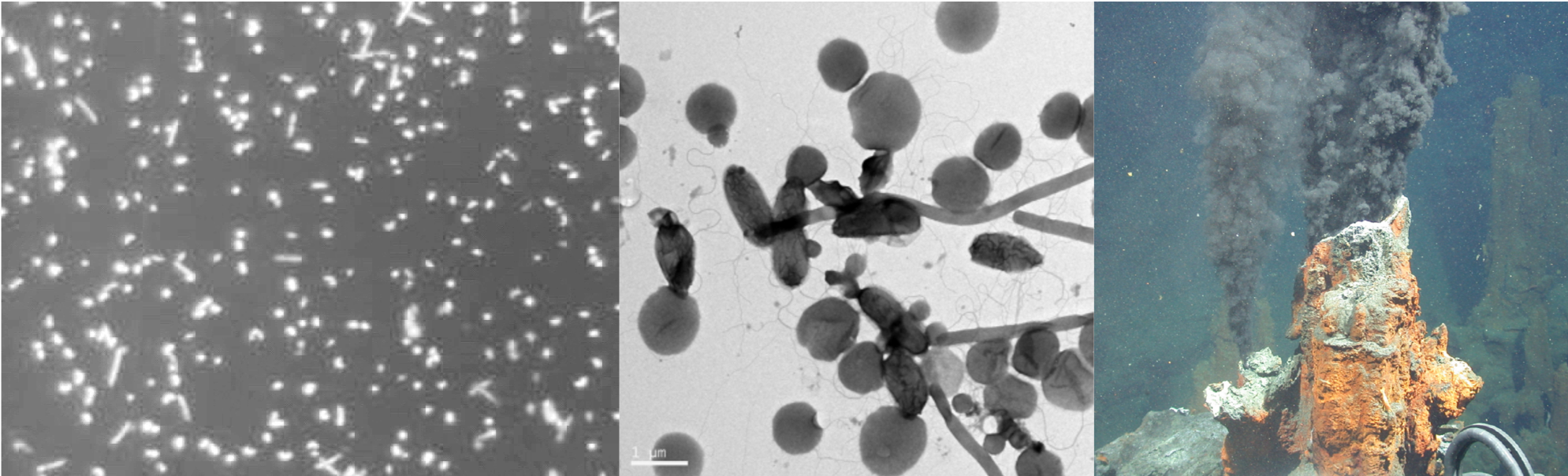

Bacteria and archaea (single-celled organisms that lack cell nuclei) make up two of the three domains of life. They might not be visible to the naked eye, but they are metabolically diverse and their activity sustain life on Earth. Ironically, the vast majority of bacteria and archaea cannot be cultured under laboratory conditions, which has caused their exclusion from formal nomenclatural structures.

These organisms are named according to the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (or “the Code”). At present, the Code only recognizes species that can be grown from cultures in laboratories – a requirement that has long been problematic for microbiologists who study bacteria and archaea in the wild.

Since the 1980s, microbiologists have used genetic sequencing techniques to sample and study DNA of microorganisms directly from the environment, across diverse habitats ranging from Earth’s icy oceans to deep underground mines to the surface of human skin. For a vast majority of these species, no method yet exists for cultivating them in a laboratory, and thus, according to the Code, they cannot be officially named.

“There has been a surge in recent years in genome-based discoveries for archaea and bacteria collected from the environment, but no system in place to formally name them, which is creating a lot of chaos and confusion in the field,” said Professor Alison Murray (Desert Research Institute, Reno). Professors Kostas Konstantinidis (Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta), Ramon Rosselló-Móra (University of the Balearic Islands, Spain) and Rudolf Amann (Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Germany) rightly noted that it remains impossible to name unculturable bacteria and archaea as long as the Code does not change or extend the nature of the required type material.

In a recent article in Nature Microbiology, an international consortium of microbiologists present the rationale for updating the existing regulations for naming new species of bacteria and archaea, and propose two possible paths forward. This international group was led by Professor Murray and comprised of scientists from across the world, including Professors Fanus Venter and Emma Steenkamp from FABI.

As a first option, the group proposes formally revising the Code to include uncultivated bacteria and archaea represented by DNA sequence information, in place of the live culture samples that are currently required. As an alternative, they propose creating an entirely separate naming system for uncultivated organisms that could be merged with the Code at some point in the future.

“For researchers in this field, the benefits of moving forward with either of these options will be huge,” said Professor Brian Hedlund (University of Nevada, Las Vegas). “We will be able to create a unified list of all of the uncultivated species that have been discovered over the last few decades and implement universal quality standards for how and when a new species should be named.”

“It sets the framework for a path forward to provide a structured way to communicate the vast untapped biodiversity of the microbial world within the scientific community and across the public domain” said Professor Anna-Louise Reysenbach (Portland State University, Oregon). “That’s why this change is so important.”

For example, researchers who use DNA sequencing to study the human microbiome – the thousands of species of bacteria and archaea that live inside and on the human body – would have a means of assigning formal names to the species they identify that are not yet represented in culture collections. This would improve the ability for researchers around the world to conduct collaborative studies on topics such as connections between diet and gut bacteria in different human populations, or to build from previous research.

The next step would be to figure out an implementation strategy for moving forward with one of the two proposed plans, while engaging the many microbiologists who contributed to this consensus statement and others around the world who want to help see this change enacted. So far, many have been eager to participate, but the overarching message is clear, we need change the system if we want to understand and meaningfully catalogue prokaryotic diversity.