Summary

- Armillaria root rot

- Pseudophaeolus root rot

- Phytophthora and Pythium root diseases

- Rhizina root disease

Armillaria root rot

Armillaria spp. have a wide host range. In South Africa, Armillaria root rot has been recorded on many hosts including commercially-grown forest species such as pines and eucalypts. It also occurs on fruit trees such as apples, peaches and citrus and on many indigenous forest tree species. When indigenous forest is cleared for afforestation, the fungus colonizes stumps, which serve as an inoculum base for the pathogen from which it can then infect plantation species.

For many years, Armillaria root rot has been ascribed to the pathogen Armillaria mellea. Recent research has shown that A. mellea is an 'aggregate' species including many discrete biological entities. The species most commonly occurring in forest plantations in South Africa is A. fuscipes (Coetzee et al., 2000).

Trees in plantations with Armillaria root rot are usually found in distinct infection centres radiating out from a single infected tree. Infection centres develop owing to the capacity of the pathogen to move from tree to tree by root contacts. Dying trees are, therefore, usually found at the periphery of the infection centres. Armillaria species can also be opportunistic and infect trees dying of other causes. In this case, infected trees are usually scattered in plantations.

Trees dying of Armillaria root rot usually have yellow (chlorotic) needles and leaves. This symptom is most evident at the end of the dry season. A flush crop of cones is often produced on dying conifers. In addition, resin or gum is usually found exuding from roots and root collars of infected trees. On eucalypts and A. mearnsii the bark at the bases of infected trees often cracks and splits open.

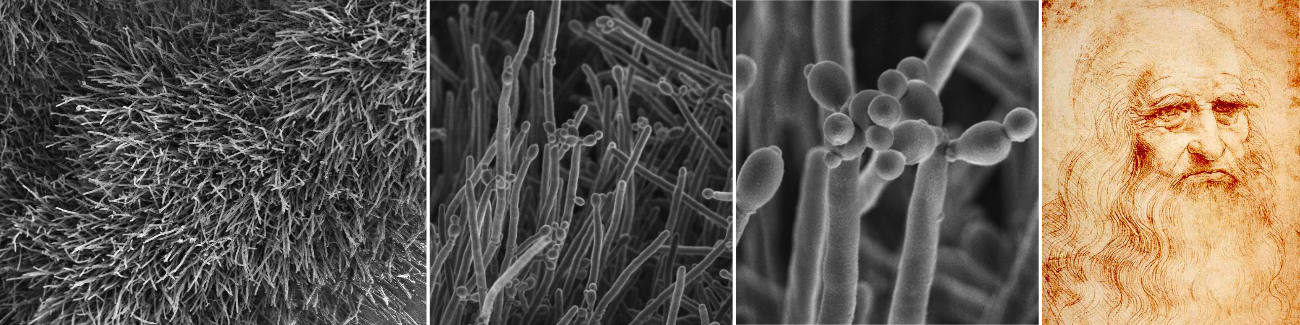

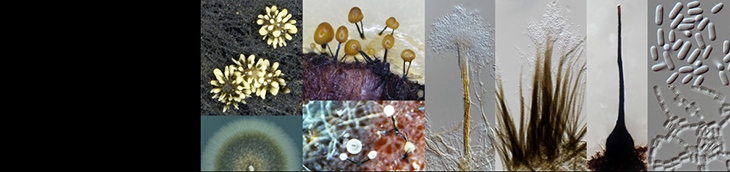

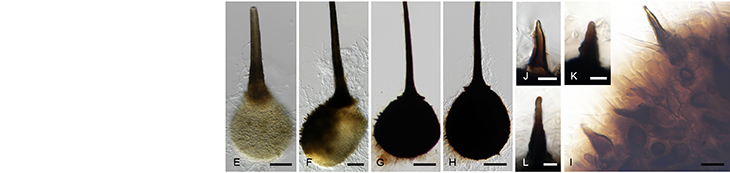

Armillaria root rot is commonly recognised by characteristic signs of the fungus. These include a thick mat of white mycelium under the bark of roots and root collars of dead and dying trees. White "fans' of mycelium may also be present. Other signs of the disease can be the presence of black "shoe-lace-like" rhizomorphs and the production of sporophores (mushrooms) near or on dying trees. Rhizomorphs (fungus roots) are structures that facilitate the movement of the fungus through the soil and from tree to tree. These are not commonly seen in South Africa. Sporophores usually have honey-coloured caps and white gills and are produced in groups at the base of dying trees. They usually occur in spring and are short-lived and thus seldom seen.

Pseudophaeolus root rot

Pseudophaeolus baudonii (Polyporus baudonii) is found only in Africa and occurs on many woody plants including indigenous and non-native trees. In South Africa, the disease caused by this fungus is known only from Zululand and all indications are that it is restricted to warm areas. In Zululand, P. baudonii is found in a small number of infection centres in pine and eucalypt plantations (Wingfield and Knox-Davies 1980). Pseudophaeolus baudonii moves from one infected tree to adjacent trees by root contacts and the symptoms of the resulting root disease are similar to those of Armillaria root rot.

Root disease caused by P. baudonii can be distinguished from other root diseases by the presence of white to yellow mycelial fans under the bark at the base of infected trees. The pathogen also produces large yellow sporophores that develop from infected roots near the base of infected trees in spring.

Phytophthora and Pythium root diseases

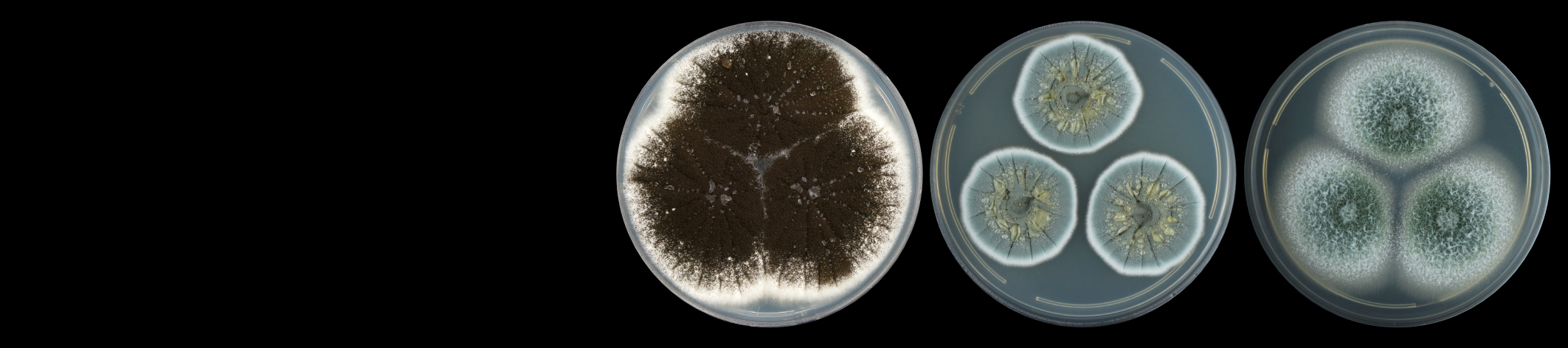

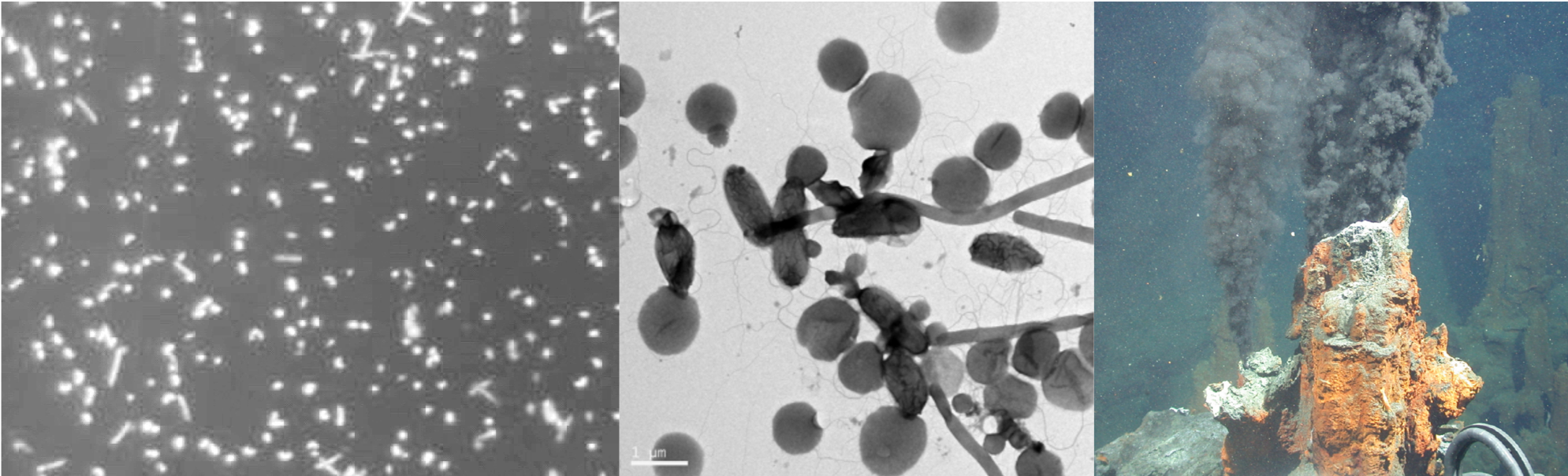

Phytophthora and Pythium species are Oomycetous water-borne micro-organisms that include some of the world's most notorious plant pathogens. These organisms, like many other root pathogens, have a wide host range and, in the case of Phytophthora, this includes many species of woody plants and forest trees. They usually do not move from infected to adjacent trees by root contacts. They rather produce motile spores that move in soil water. Dying trees are usually scattered in plantations, although small patches can also be present. Roots of diseased trees have rotten bark, which easily slips off woody parts.

The most obvious symptom on trees infected with Phytophthora and Pythium species is a general wilting of the leaves. This can be preceded by a reddening and then chlorosis of the leaves. Rapid wilting is characteristic of trees that have become girdled at the root collar, particularly during hot and comparatively dry periods in summer.

Phytophthora root disease has been found on various species of pines and eucalypts, as well as on wattle in South Africa (Linde et al., 1994). On pines, P. cinnamomi is the most common species associated with disease. In many cases, inoculum has been transferred with plants from infected nurseries. Severe disease has been recorded on Pinus radiata on poorly-drained sites in the southern Cape and on a trial planting of P. clausa in Zululand.

A number of Eucalyptus species including E. fastigata, E. fraxinoides, E. smithii and E. nitens are known to suffer from serious root and root collar disease problems caused by P. cinnamomi. The current view is that the disease is of a complex nature and recent research has identified at least three other Phytophthora spp. involved with disease of eucalypts in South Africa.

Basal canker and gummosis is a common disease of Acacia mearnsii in South Africa. In many cases, this disease is caused by Phytophthora nicotianae. A number of other Phytophthora spp. are associated with basal canker on wattle. There are indications that, where wattle planting has preceded establishment of eucalypts, P. nicotianeae can cause disease of these trees.

Pythium splendens has caused severe losses in young E. grandis clones in Zululand. Symptoms of this disease are similar to those associated with Phytophthora spp.

Serious problems have been experienced in establishing pines on old agricultural lands in the Eastern Cape. This disease problem is absent in plantings on adjacent virgin lands. Pythium irregulare is consistently associated with, and believed to be one of the important factors contributing to this disease. Indications are that populations of this pathogen have built up on previous rotations of agricultural crops.

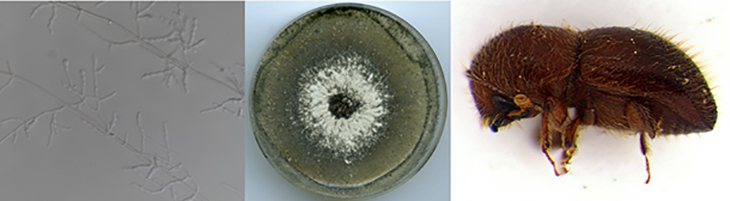

Rhizina root disease

Rhizina undulata causes "group dying" of conifers on burnt sites (Wingfield and Knox-Davies 1980; Germishuizen 1984). Sporophores of the fungus are irregularly lobed, red to dark brown and are formed after fires in pine plantations or on areas that have been clearfelled and burnt. In Southern Africa, Rhizina root disease has been serious, particularly in the Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, North Eastern Cape and Swaziland where seedlings have been planted shortly after slash burning. The disease is specific to conifers and can only be recognised by its association with fires and the presence of sporophores of the fungus, which are a red brown colour when fresh and turn dark brown to black as they dry out. The disease occurs only where there has been a previous rotation of pines. Thus, burning of veld or indigenous brush prior to planting poses no danger.